by Dr. Ryan Nichols, Philosophy, Cal State Fullerton, Orange County CA

The surprising robustness of AntConc to do interesting analyses and dig deep into sets of texts is immediately apparent when putting the concordance tool to work. We left off last post noting some discoveries from our exploration of Joyce’s early novels with AntConc’s clustering tool. Using the same three novels, now we’ll go into more detail about the role of God in them.

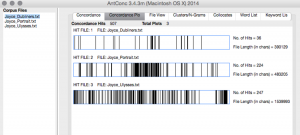

To get a better sense of the role of God in Dubliners, Portrait, and Ulysses, let’s first capture a bird’s eye point of view on its dispersal through the three works. Loading them back into AntConc, in Concordance view, we enter ‘God’ into the search bar. Up comes a window of all the sentences in which that term occurs in the novels. But now toggle to Concordance Pro view, and you will see this image:

We can identify some differences between the novels’ use of ‘God’ by noting that Ulysses disperses ‘God’ throughout the length of the novel, though with a gap near the end. This contrasts with the other two works, where the term is less evenly represented. Portrait, though, has a dense, telling representation of the word in the middle. Ulysses closes with its most dense representation of this term.

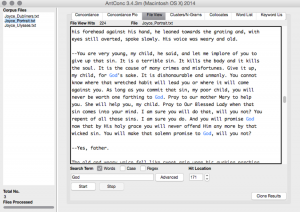

Those who know the novels can begin to map these patterns easily onto content. Consider Portrait. In the middle of the book, as Stephen sits in the pew, thinking about memories of his childhood, Father Arnall offers a homily of sorts at the beginning of the boys’ retreat. This part of the book culminates in Stephen going to confession for the first time in a long time. This is probably the section with dense representations of ‘God’ in the middle of the book. We can find out for sure simply by clicking on one of the thick black filaments in the horizontal bar representing Portrait. By doing so, AntConc brings us to File View:

This might give the impression that ‘God’, for Joyce, is associated with negative words, words like ‘crimes’, ‘misfortunes’, and ‘dishonourable’. Indeed, several scholars in the secondary literature have discussed Joyce’s negative view of God and Catholicism. It is one thing to say this on the basis of close interpretations of dramatic, attention-getting scenes like this fateful event in the confession booth. But it is another to show that this association is true by testing it with text analytics. So is God as represented in Joyce’s early novels represented negatively or with a negative moral valence?

This question brings us to some of AntConc’s most useful features. Leaving all three books loaded in, click over to the Collocates tab. This area will allow us to identify words that ‘God’ appears with in the texts. In turn, this will provide us data with which to draw influences about, for example, the moral valence of God in early Joyce novels. AntConc offers us several particulars we can manually set. These include the word window span left, the word window span right, the minimum collocate frequency, and the test statistic with which we want to sort our results. ‘Window span’ refers to the range of words, separated by spaces, to the left or the right of the target word. Setting the window span at 5 left and 5 right is good for starters. But given English grammar, authors might describe or discuss God using words that are >5 away from the token ‘God’. So we might want to expand it later for good measure.

The default “Sort By” is “Stat”. And the default test statistic is MI, or Mutual Information. Mutual Information represents a ratio of the observed frequency (fo) of the combination of two words (or two word phrases) divided by the expected frequency (fe) of the combination: fo / fe . Sometimes this result is converted into base 2 (see: Bieber, Quantative Methods in Corpus Linguistics). The expected frequency is the frequency supposing the combination were to occur by chance. The observed frequency, of course, is the actual number of times the two words co-occur in the corpus. (AntConc also supports T-scores, which are used to assess the dissimilarity of collocates between two terms. For reasons we will enter into in a later post, T-scores are not the best test statistic for colocation studies.) To toggle between one or the other, go to Settings/Tool Preferences/Options. AntConc also allows you to sort by frequency, frequency on the left or on the right (useful when looking for relations via parts of speech)

To get a sense for the utility of the AntConc Concordance tool for your own research, please note the differences between MI-score outputs and T-score outputs. To generate this pair of outputs, I left the defaults as they were, and set the minimum colocation frequency as 2. See the two tables below.

MI Collocates with ‘God’ in Dubliners, Portrait, & Ulysses

| Rank | Freq | FreqL | FreqR | MI | Collocate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 10.7387 | enlighten |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 10.7387 | cherubim |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 10.3236 | displease |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9.73870 | thoth |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 9.73870 | reigneth |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9.73870 | inalienably |

| 7 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 9.32366 | omnipotent |

| 8 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 9.20818 | almighty |

| 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9.00173 | dieu |

| 10 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 8.80581 | bless |

| 11 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8.73870 | merciful |

| 12 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8.73870 | catholics |

| 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8.73870 | begotten |

| 14 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 8.54605 | declare |

| 15 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 8.44919 | created |

T-score Collocates with ‘God’ in Dubliners, Portrait, & Ulysses

| Rank | Freq | FreqL | FreqR | MI | Collocate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 262 | 165 | 97 | 14.34391 | the |

| 2 | 173 | 130 | 43 | 11.95026 | of |

| 3 | 151 | 82 | 69 | 11.44190 | to |

| 4 | 151 | 75 | 76 | 11.04698 | and |

| 5 | 92 | 15 | 77 | 9.10928 | s |

| 6 | 93 | 24 | 69 | 8.69440 | he |

| 7 | 94 | 47 | 47 | 8.45890 | a |

| 8 | 75 | 21 | 54 | 8.06571 | i |

| 9 | 73 | 31 | 42 | 7.68971 | his |

| 10 | 69 | 34 | 35 | 7.66831 | that |

| 11 | 63 | 56 | 7 | 7.64881 | by |

| 12 | 66 | 27 | 39 | 7.49530 | was |

| 13 | 59 | 18 | 41 | 7.16244 | you |

| 14 | 56 | 34 | 22 | 7.00579 | for |

| 15 | 65 | 32 | 33 | 6.94264 | in |

These columns of data are almost self-explanatory, given their names. However, the Freq column deserves a word. This column refers to how many times the collocate appears in the targeted word window. In this case ‘enlighten’ appears twice within 5L/5R of ‘God’.

Information from calculation of the Mutual Information score, however, appears quite useful. We learn from the first of the tables above that ‘God’ appears to be surrounded by rather positive terms. But MI can also be misleading.

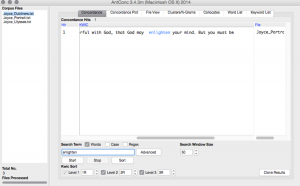

Consider ‘enlighten’ again. This term appears to occur twice within 5L/5R of ‘God’. Let’s find out for ourselves by clearing the search window, toggling the Concordance bar, and typing ‘enlighten’. Here we find that we have only a single occurrence of that word in all three books.

When we click on the sentence, we can read in File View this: ” And let you, Stephen, make a novena to your holy patron saint, the first martyr, who is very powerful with God, that God may enlighten your mind. But you must be quite sure, Stephen, that you have a vocation because it would be terrible if you found afterwards that you had none.” ‘Enlighten’ has earned its MI of 10.7 by occurring a single time in the entire corpus, but by occurring next to two different tokens of ‘God’. This does not appear to be an important collocate of ‘God’ after all.

Now that we have identified a problem we can do something about it. Let’s return to the collocate window. This time, in the “Min. Collocate Frequency” box, set the value to 10. This way we will avoid focusing on under-representative colocations.

MI Collocates at 10 LR with ‘God’ in Dubliners, Portrait, & Ulysses

| Rank | Freq | FreqL | FreqR | MI | Collocate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 9.36018 | almighty |

| 2 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 8.80581 | bless |

| 3 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 7.84057 | prayed |

| 4 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 7.81270 | souls |

| 5 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 7.68425 | pray |

| 6 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 7.51630 | save |

| 7 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 7.21032 | help |

| 8 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 7.17576 | grace |

| 9 | 82 | 41 | 41 | 7.11041 | god |

| 10 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 7.04838 | blessed |

| 11 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 7.00534 | sin |

| 12 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 6.98381 | knows |

| 13 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 6.68807 | holy |

| 14 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 6.53992 | instant |

| 15 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 6.50029 | cried |

The result, pictured above, indicates that the most frequent collocates of ‘God’ represent a wide mix of parts of speech. On the whole, the terms have a very positive valence. With occurrences on the right side of the term, we infer that Joyce’s God does a lot of blessing (rank 1), a lot of knowing (rank 4), and a lot of making (rank 14). This raises some doubt about scholarly claims to the effect that God in Joyce’s early novels is primarily dour or punishing. Of course this is only the first step in a longer journey to evaluate such a claim. We might, next, click on certain collocates to view them in File View. But I leave that as homework of a sort.

In the next post we will work on using AntConc to examine contrasts in word use between different texts.